Modelling in practice is a new series at DHI that explores how environmental models are being applied to support better decisions for our environment.

In this Q&A, we are joined by Jonas Brandi Mortensen, Senior Environmental Scientist, to discuss agent-based modelling (ABM): what it is, where it is useful and how it is being applied in environmental and water management today.

Q: For someone who’s never heard of the term before, what is agent-based modelling, in plain language?

I think one way to think about it, is that agent-based modelling is a way to simulate a system by modelling many individuals, like animals, people or boats, one by one. Every ‘agent’ follows rules based on its traits and what it encounters, such as competitors, habitat or food. When you let lots of individuals interact over time, larger patterns emerge, like where different size classes of fish tend to live or how they spread across a reef.

For example, in a reef, large cods might dominate the best shelter, and smaller cod might be pushed into less optimal areas until they grow bigger. An agent-based model represents each fish as an individual with traits like size, and rules like ‘compete for shelter’ or ‘avoid dominant fish’. When many fish follow these rules, the model can reproduce the spatial patterns we observe across different size classes.

This differs from classic population models that treat the whole population as one average fish, because it can capture how individual differences and interactions drive the overall outcome.

Q: In your field of work, i.e., biodiversity and ecological modelling, what do the ‘agents’ usually represent, and what kinds of behaviours do you model?

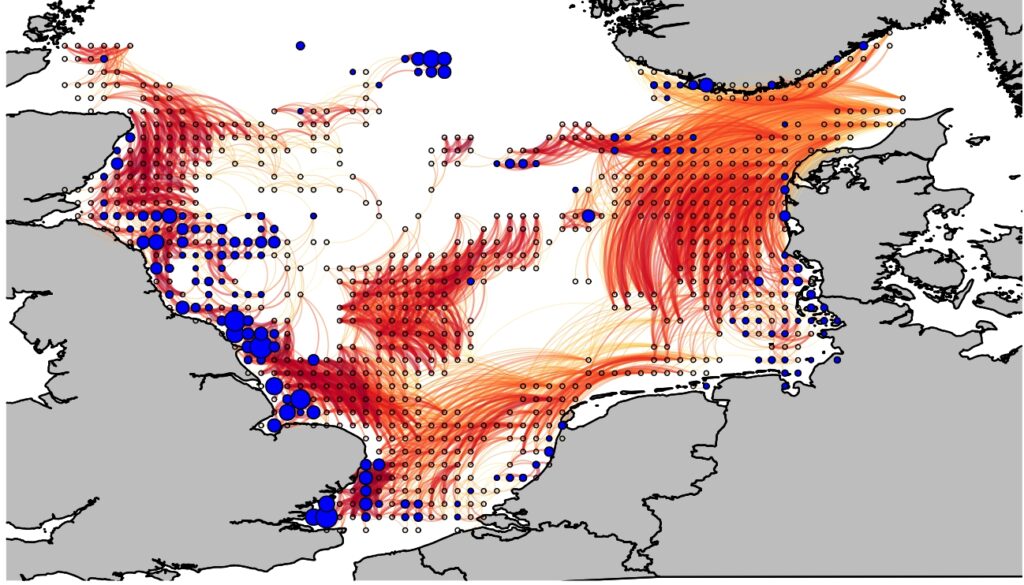

Normally it is something really big like the seasonal migration of marine mammals, or something very small like coral larvae to understand how coral reefs are ‘connected’ genetically. Marine mammals tend to have the most complex behavioural rules, such as the difficult decision to abandon your calf if your own blubber reserves are running low or remembering the location of breathing holes in drifting ice sheets in the Arctic. How they respond to underwater noise from shipping and offshore development is typically the key question though, and because we model the population as individuals, we can quantify the noise exposure on an individual level relative to their interaction with the environment.

Coral larvae and other pelagic propagules tend to have simpler rules which affects their ability to swim and settle compared to our marine mammal models. But the more you dig into the biological details, there’s plenty to account for as well. This could be life-stage dependent change in buoyancy, food-dependent rate of development, the ability to sense existing reef and swim actively towards even if you’re just a teeny tiny larva.

Q: What kinds of insights about water environments can ABM reveal that are hard to capture with averages or equations?

Oh, that’s difficult to answer briefly. In a marine context, a useful rule of thumb is that ABMs are most valuable when you are modelling discrete individuals or objects, rather than something that behaves like a continuous substance, and when the number of entities is manageable (for example, thousands of whales rather than trillions of sand grains). They are particularly helpful when you expect strong individual variability in behaviour, exposure or movement. That said, it is always case-specific, and the right modelling approach ultimately depends on what decision the model needs to support.

To give a concrete example, let’s talk whale densities and offshore windfarms. Sometimes I see disturbance impact calculations made by using an annual average density of a given whale specie and multiply that with an impact area to get the number of disturbed individuals. But if it’s a migratory specie, the chances are that the whale is only present in the area a few months of the year. As such, you risk overestimating the impact if the construction schedule is during months where the whales are not present at all, or maybe worse, you risk underestimating the impact if the construction is planned right in at the peak of migration.

An agent-based model can account for this spatiotemporal variability in marine mammal distributions but also the construction schedule and the associated underwater noise, and the result is a more realistic and accurate prediction.

Q: Where is ABM currently being applied in water and environmental management, and what kinds of decisions can it support?

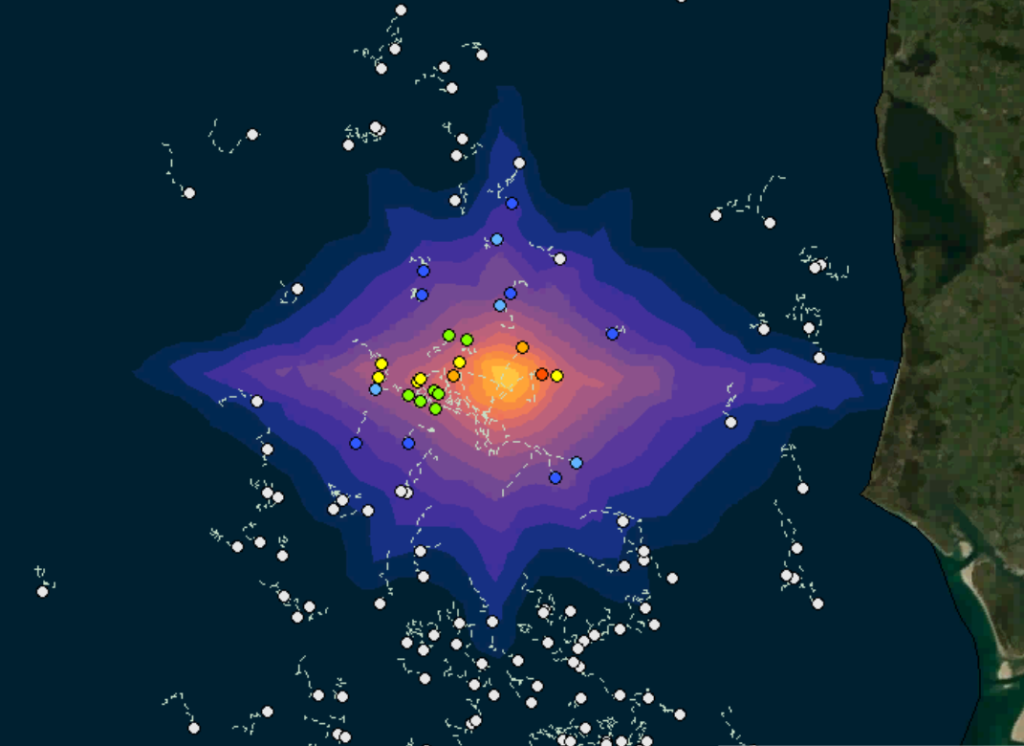

ABMs are quite widespread in DHI. Our megafauna models feed directly into EIAs of various kinds, typically centred around underwater noise disturbance, while our marine habitat connectivity models provide insights into both nature restoration efforts as well quantifying the risk of invasive species spreading. We also use ABMs for identifying likely accumulation and impact zones for plastic debris, sargassum seaweed or oil spills. Finally, a growing number of modellers in DHI are using ABMs for vessels – in fact, the NCOS Solution by DHI SeaPort is essentially an ABM.

So, whether it’s responding to an oil spill, designing a new marine park or optimising your OWF construction schedule, an ABM is a valuable tool to apply.

Q: From your own work, what first drew you to agent-based modelling, and what continues to fascinate you about it today?

I still remember the exact moment – It was during my internship with DHI in 2008, my future mentor, Flemming T. Hansen, showed an animation during a knowledge-sharing session that was probably the first agent-based modelling animation in a DHI context: fish larvae being flushed through a Danish creek. As a young, aspiring marine biologist, watching those dots move with the currents, something just clicked, and I knew this was the direction I wanted my future work to take.

A few years later, I managed to convince an Australian university to sponsor a two-year research programme aimed at building the world’s first bull shark ABM as part of my Master by Research programme. The model of course didn’t quite work as intended, but I learned a lot. Later, when I joined the R&D Department at DHI Singapore in 2012, I had plenty of opportunities to help build many of DHI’s first-generation ABMs, which was a wild ride for me. Since then, many models have been built, tested and reported, and while I sometimes get distracted by other types of modelling, the versatility, transparency and flexibility of ABMs mean they will always be my favourite kind of model.

Connect with Jonas Brandi Mortensen on LinkedIn

Know more about DHI’s technologies in agent-based modelling: https://www.dhigroup.com/technologies/mikepoweredbydhi/abm-lab