The role of hydraulic models in risk assessment analysis

Most hydraulic models provide a ‘water age’ option that allows users to calculate the residence time of water within the pipe network. While this is a standard water quality indicator used in practice, it does not address the issue when we need to analyse the contact time with pipes of a specific material, such as polyvinyl chloride (PVC).

Why is it important to analyse contact time with a material like PVC?

Vinyl Chloride Monomer (VCM) – a synthetic chemical that presents itself as a colourless and odourless gas at ambient temperature and pressure – is one of the reasons for the need for such analyses. Usually, VCM is fully polymerised in the PVC with only a very low content of the residual monomer being able to migrate from the pipe into the drinking water. Vinyl chloride in water usually evaporates rapidly when near a surface and has low solubility in water. However, VCM in its unaltered state is a carcinogenic substance to humans and is regulated in drinking water as well as in food and air.

VCM is potentially released through the PVC glue subjected to bad polymerisation in pipes built between 1960 and 1980. As hazardous levels of migrating substances may be exceeded for water that has been in contact with the material for more than 48 hours, water authorities will benefit from knowing the accumulated time of contact between the water and such pipes. The flow of water through newer PVC pipes usually adds very low amounts of vinyl chloride to water and is not recognised to pose any risk. However, even newer pipes of other materials such as polyethylene (PE) may give cause migration of other problematic substances.

Despite the approval schemes in different European countries, several pipe materials are found to leak other unwanted substances. An example of this is some of the degradation products of the used antioxidants, many of which are considered as endocrine disruptors (substances that may interfere with the human hormone system).

Safeguarding public health and safety

The presence of hazardous substances migrating from drinking water installations including VCM from PVC depends on the manufacturing process as well as the quality of the raw material. As a result, the pipe quality varies according to the suppliers and cannot be assumed. The European Commission’s Drinking Water Directive 98/83/CE states a threshold limit value of 0.5 µg vinyl chloride/L in drinking water, which is today’s maximum level for all EU member states.

In the WHO guidelines for drinking water, a threshold limit value for VCM has been set and lowered through the last 25 years and today, the guideline value is set to 0.3/L in drinking water. However, for a lot of substances, no maximum limits have been set, neither in the EU Directive nor in national requirements. Most countries have quality criteria for new installations but not for all relevant substances. With regard to older pipes, it is most likely that evaluations have never been carried out.

A 2011 decree passed in France mandates that random samplings on the network must be made by the Agences Régionales de Santé (ARS – France’s regional health agencies) to determine the level of VCM in the water. When the level is higher than 0.5 µg/L, the network owner, i.e., the city, is required to change their pipes and eliminate the sanitary intoxication within three months. If this condition is not met, they may simply put a stop to all water distribution.

To safeguard public health and safety, the ARS strongly recommends implementing a model to determine the risk of VCM in drinking water, especially for cities where the carcinogenic molecule has been detected.

A new computational method to analyse cumulative contact time

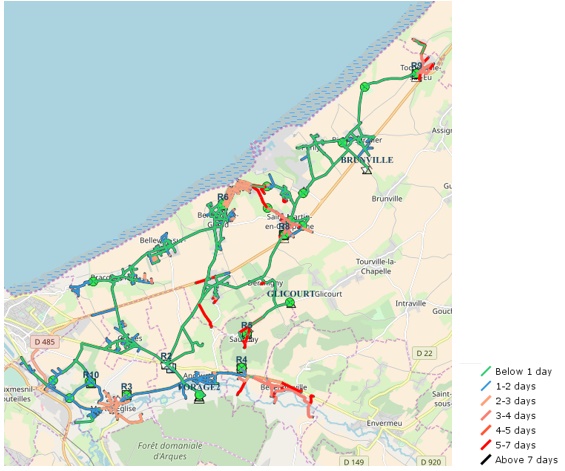

To analyse the contact time with pipes of a specific material such as PVC, a new computational method was introduced that supports the residence time accounting specifically for plastic pipes. The results of the simulation are shown in the illustration below where pipes are colour-coded by a value corresponding to the amount of time the water was in contact with PVC pipes.

Pipes marked as green/blue are pipes where the contact time with PVC material is less than 48 hours. Pipes in orange/red are pipes where there is a risk of unhealthy concentration of VCM released from the PVC pipes. © DHI

Curious to learn more?

Find out how you may better manage your water network with the WaterNet Advisor. Link up with us for details.

About the authors

Petr Ingeduld

Senior project manager and hydraulic engineer, DHI Czech Republic

Petr is a water supply systems expert at DHI with over 20 years of professional experience. Throughout his career, Petr has focused on the development and application of hydraulic models to support water supply and distribution. He has managed numerous global projects and provided technical direction and troubleshooting on various modelling efforts.

Mortadha Guermiti

Project engineer, DHI France

A double engineering degree holder between France and Tunisa, Mortadha is a subject matter expert on the modelling of drinking water supply networks. He is especially knowledgeable in the risks of vinyl chloride monomer (VCM) and possesses prior experience in roles relation to water, environment and hydraulics.

Lise M Møller

Senior scientist, DHI Denmark

Lise is specialised in exposure and toxicological risk assessments of chemicals in industrial products and consumer articles. Her expertise also includes endocrine disruptors, environmental risk assessment of chemicals and development of environmental quality standards. Lise has more than 15 years of experience in assessing health effects from polymer materials in contact with drinking water.